Creating an APS culture that allows for mistakes and learning as a platform for innovation and stewardship

Originally published in The Mandarin

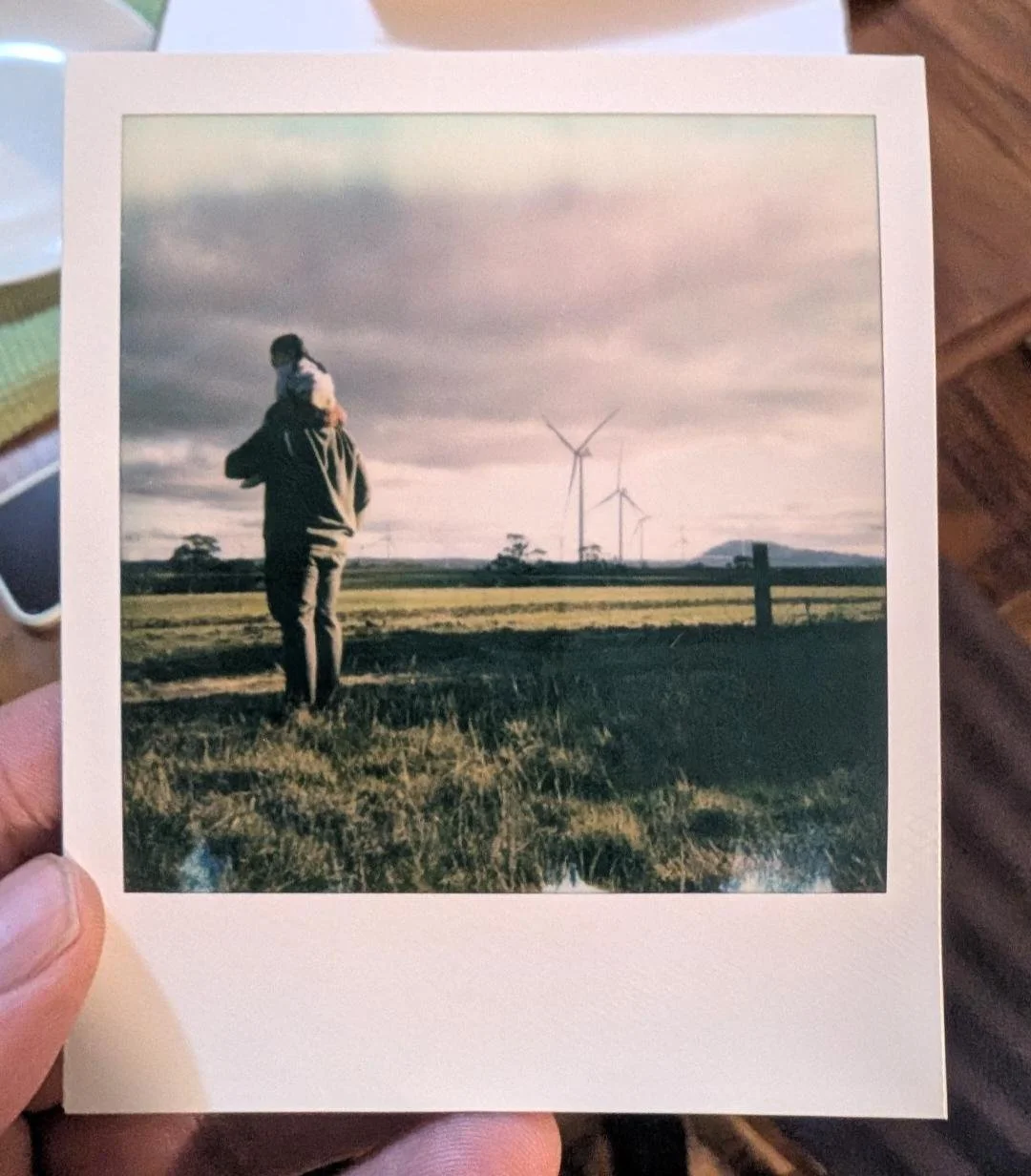

If incompetence, laziness, arrogance or disinterest are why people hide mistakes, the solution may be in coaching and performance management. (Zennie/Private MEdia)

In an excited moment during The Mandarin’s recent “Rebuilding Trust and Integrity in the APS” conference, I promised an article with the above headline via a LinkedIn post.

I added ‘stewardship’ to the title because APS commissioner Dr Gordon de Brouwer told us it’s a potential sixth value for the APS. It also fits well with the ‘learning from mistakes’ theme.

Next, I set about trying to find something new on this topic. Surely there was some recent research that I could centre the discussion around.

Then I asked myself if there is really anything new here, or if we are just not applying the basics of what we already know.

Some of these basics were expressed very well by conference speakers.

De Brouwer told us: “Mistakes are not the problem — that’s how we learn and improve.

Hiding them is a problem.”

Minister Bill Shorten reminded APS leaders that: “An agency’s culture is set from the top; to think big; to seek insight, not just confirmation of your own biases; and encourage news you need to hear, not just what you want to hear.”

Then he added — and this was my favourite advice of the conference – “Avoid a culture of entrenched stupidity”.

Then ‘stewardship’ emerged as a potential new APS value, where public servants are genuinely empowered to trial, test and learn valuable lessons — from successes, failures and all those bits in between.

The key is then to have the mechanisms in place to effectively share those lessons to continuously build the body of public service knowledge — to improve today’s decisions and to provide data and information for future generations.

You can’t do any of the above if you’re in fear of revealing a mistake or sharing a lesson.

It all makes so much sense. With all due respect to the speakers, because we obviously need to be reminded, there’s nothing new here.

The pressing question remains: how do we create a culture where public servants are confident to make mistakes — and not hide them?

Before answering that, let’s look at what a mistake is — because I think that’s where some of the problem lies.

If your mistake is a result of inadequate preparation, research, collaboration, risk assessment … or you had a big night, took a shortcut, didn’t ask for help when you needed it, or considered advice when it was relevant, or if you thought you could just wing it …

… well, these are all personal lessons you need to learn as early in your career as you can, and preferably before you apply for your second job.

I don’t think these are mistakes, really, but more a demonstration of incompetence or laziness, arrogance or disinterest. From a career perspective, there may be good reason to try to hide them.

If that’s why people hide their mistakes, then the solution may lie more in coaching, mentoring, training and performance management than anywhere else.

Then there are the mistakes that are made where not all information could be available, but as much preparation as possible had been done, risks had been assessed as far as they could be, scenarios had been run, but rather than freeze in indecision, a decision was made — and it didn’t turn out well.

These are the highly valuable, deeper lessons we need to learn, capture, share and — as stewards — contribute to the APS body of knowledge so that future decision-makers can draw upon them to improve their understanding or situational awareness.

Getting back to the question about creating a culture where public servants are confident to make mistakes, I think part of the answer lies in the type of ‘mistake’ you are making.

If it’s the first type, then you need to lift your game. If it’s the second, then I think we start by remembering that this is what the APS wants and needs. Then it’s about establishing the ground rules and learning, and sharing processes to support leaders who make a mistake.

When Shorten and de Brouwer both publicly state that they want it, you have some decent backing to make the changes required.

Critically, senior leadership needs to set the tone and tolerance for how the organisation responds to and learns from mistakes.

These leaders need to be brave enough to adopt and role model desired behaviours when a mistake occurs — from their initial response to their proactive support for and participation in the processes and tools required to capture and share the lessons.

They need to show that mistakes help us to learn, evolve and innovate instead of stagnate, and through these demonstrations, give their middle managers permission to do the same.

Everyone in the system needs to feel psychologically safe. This is difficult to achieve, especially when one moment of inappropriately expressed frustration or anger, one negative judgement on the mistake-maker’s capability, one side-comment to a colleague about their performance, or one blaming statement can unravel every good intention and break trust that will be harder to regain.

It can feel like a house of cards and each card needs to hold its position well.

Psychological safety needs to be supported by human resource policies, and practice processes and tools.

Then everyone needs to learn from the small mistakes, recognising them as learning opportunities, so that when a big one comes along, the skills and mindsets are in place.

This might involve adding a ‘lessons’ item to your agenda. I’ve heard of one organisation that runs a “Fail Friday” meeting where they discuss their mistakes, lessons and recovery strategies. Another organisation used “War Stories” where executives would share a story of a career mistake and their recovery approach in a monthly forum.

This could be supported by adjustments to your performance management tools, recruitment approaches and your employer value proposition.

Some thought may also need to go into how the organisation defines, expresses and deploys its risk tolerance. This will influence how willing decision-makers are to make their decisions in certain circumstances.

Deploying decisions down to more junior levels, as is reasonable, will also empower and train emerging leaders on how to take calculated risks, within organisational guardrails, on smaller matters, before being faced with bigger ones.

There may also be some education required around the similarities and differences between being decisive and being a good decision-maker, and the benefits of “fail fast, fail early”.

If you can make a well-informed decision going in, then when enough or more information comes to light to let you know it was a mistake, don’t double down — make that second well-informed decision to go a different way.

I’m finishing with a reminder of de Brouwer’s message: “Mistakes are not the problem — that’s how we learn and improve. Hiding them is a problem.”