Who are you at the communications barbecue?

Originally published in The Mandarin

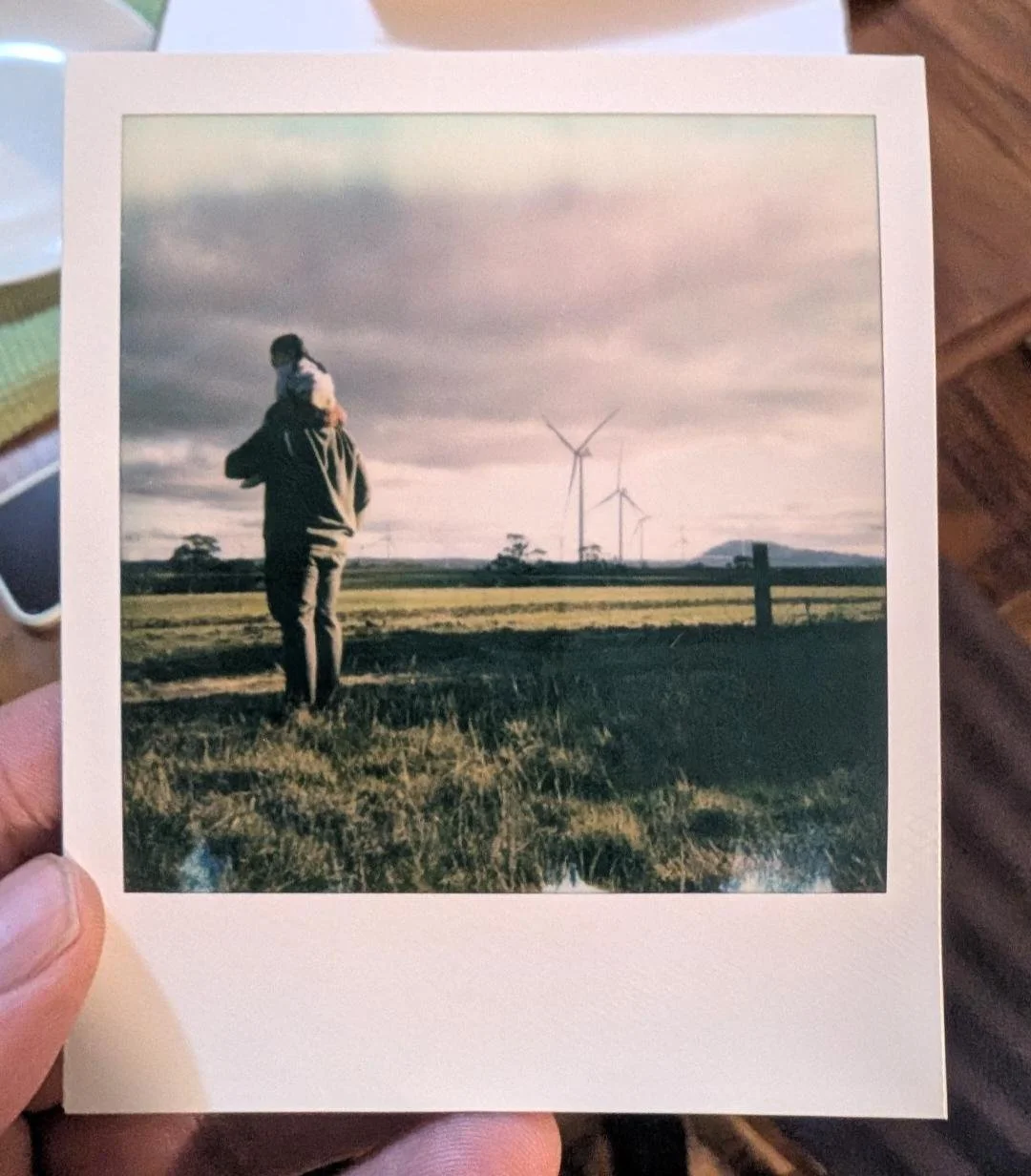

Sometimes communication is that person at the BBQ with the big hat and a drink in hand. (Madeleine McMahon)

Sometimes communication is that person at the barbecue with the big hat and a drink in hand, talking a lot to anyone and everyone, not quite hearing their replies, lacking a bit of insight, but connecting here and there, and having a great afternoon.

Strategic communication is the person who knows the names of everyone there, what they like to eat and drink, as well as the award their kid just won. They timed the barbecue after the kids’ sport but before the match on TV. They’ve catered for vegans and celiacs, but there’s also plenty of steak. Everyone knows this person and is willing to help them out if asked.

The one with the big hat is likeable enough, we can take or leave them, and while the organised one is a bit less fun sometimes, their efforts are valued and seen as helpful — we need them to keep us all on track, to get the results, recognising that without them, there is no barbecue.

As a leader approving multi-million-dollar communication budgets those comparisons might seem a bit flippant — but if you’ve just had flashes of chatty-big-hat-at-BBQ … stay tuned.

The key to strategic communication — internal and external — is that it has a very clear purpose. You know very specifically why you’re doing it, you plan very carefully how you’ll do it based on the particular audience you’re seeking to influence. You calculate the organisational value of the objective to be achieved and the investment you’ll make, and once you’ve done it — in a very precise way — you’ll measure your success in terms of effectiveness against that predefined objective. You’ll measure what your target audience is thinking, feeling or doing differently, and thus the return on your investment.

Strategic communication relies on research, experience and psychology, and employs a suite of tools and techniques to create the impact or adjust the thinking or behaviour of your target audience — all so that your organisation can achieve its strategic organisational objectives — and that line between strategic objectives and communications objectives is a tight one.

The first question a strategic communicator asks is: why are we doing this, and why are we doing it now? Which organisational priority are we supporting and what do we need our target audience to think, feel and do to support that priority?

Then we ask, who are our targets, the ones who can have the most positive impact on the organisational priority; and where are they physically, technologically, logically and emotionally… and where do we need them to be?

It’s easy at this point to focus more on an internal or external audience, but engagement with these communities needs to run in parallel, fully harmonised. If you’re leaving breadcrumbs or signalling for one, you have to be doing the same for the other, and ideally, your internal audiences should have at least the same level of information earlier, not only to maintain their support but to set them up as advocates and communicators for your purpose.

Sometimes these are easy questions to answer, and at other times, just like the movie, your target audiences are here, there and everywhere — and you need to accommodate that, making sure that you reach them, where they like to be reached, probably across several channels or platforms, at times that work for them, with consistent, coherent, integrated messaging.

Your message crafting is also borne of research, to inform your language, the length of your sentences or reels, the colours of your visuals, and the frequency of touch points. You also need to pay attention to what is really relevant and useful to your audience, don’t overwhelm them just because you are fascinated — remember you’re trying to guide them to think, feel or do something that is more favourable to your objectives. Stop there.

Then you have to work out how to hear them. Are they clicking, sharing, responding to your call to action, talking about you, or in some cases have they stopped talking about you? Once you’ve heard from them, what will you do with that information, what can you learn, and how will it inform ongoing adjustments and improvements to your communications approach or plan?

If that all sounds reasonable and simple so far, let’s stretch it to a more likely multi-division, multi-program environment where strategic and tactical alignment and integration provide an extra layer to be managed.

This is more often where strategic communication loses its way, for many reasons.

Sometimes it’s because structurally, there are no clearly defined, stated or mandated strategic objectives at the organisation or program levels to guide communication objectives at the lower levels.

This absence of shared strategic objectives leads to dispersed, localised priorities, inconsistent messaging, multiple channels, conflicting timing, competing narratives, bombarded audiences and just a lot of annoying noise and confusion that undermines everyone’s efforts, and offers no return on any investment.

When the executive is not clearly communicating the strategic priorities and creating a single source of truth for an organisation or program, and ideally an overarching structure to guide the dispersed communications effort, it typically leads to a situation where dispersed divisions, programs and/or projects seek to set the direction to the best of their ability, from the perspective of their lower-order priorities. They may do an excellent job at that more operational or tactical level, but they are very likely to compete for audience attention with other areas, who are also promoting their own lower-level interests.

If we want to add another typical layer of difficulty, let’s consider that this often happens in a multi-vendor environment where suppliers are contracted to deliver very specific results at a lower level (eg project level) and are then required to jostle for position in a competitive rather than collaborative way. That’s often how the system is set up.

These very same scenarios can arise with stakeholder engagement.

I’ve worked in strategic communications for decades, and these scenarios are very real. I’ve also worked on major programs where each multi-million-dollar project is focused on its own objectives to the detriment of the collective and strategic program and/or organisational objectives.

It’s a vicious circle because those projects and their communications leads are required to report against project and program objectives, and no one wants to report red, even if ignoring these issues will threaten the ultimate success of the collective program.

This applies equally to internal and external communications, although internal stakeholders are often overlooked on larger projects, as is the value they can bring as well-informed parties within your sector.

Typically, when you arrive at this situation, you invest significant funds into alignment and integration activities which if you’d set things up well in the beginning, would not be necessary.

So, there’s the problem definition. What about a solution?

If you are a communications professional who has avoided these scenarios over a long career — well done and please message me. If some of it sounds familiar, and even if you’re in the thick of it right now, there’s a simple way out.

Review everything you are doing and see how it maps through your project and program to benefits and organisational strategy. If what you are doing does not align, have the chat with the person spending the money to plan how you will realign your plans.

You may be ‘rocking the boat’, and you may have to ask parallel projects or initiatives to realign with you, but if they want to communicate strategically, for the good of the organisation, not just your monthly report or siloed outcomes, then you need to do it, and everyone should thank you for it.

Remember, there are two types of people at the BBQ. Be the one who drives the results.