UK civil service is a masterclass in service delivery

Originally published in The Mandarin

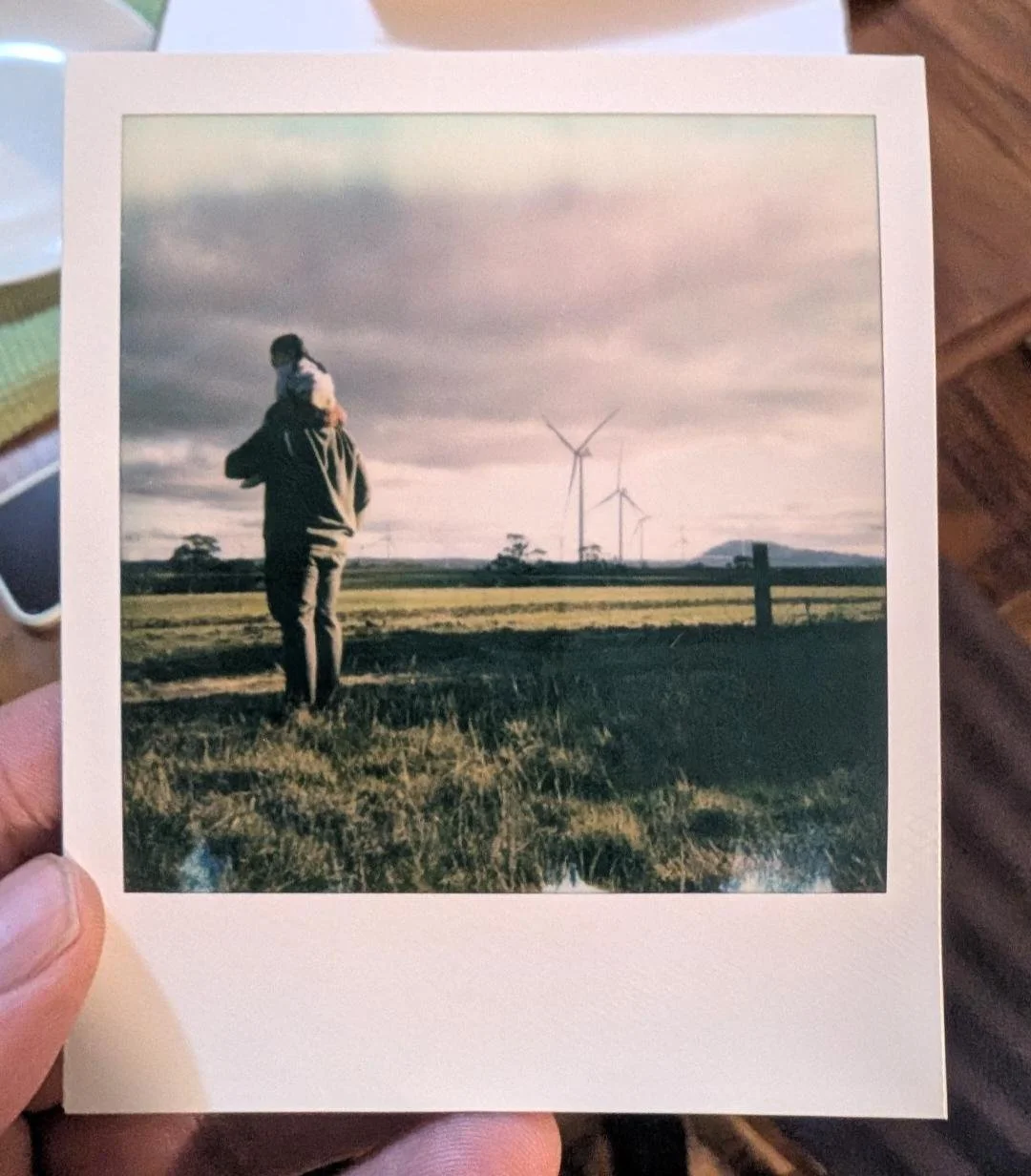

A user journey through the UK bureaucracy. (Zennie/Private Media)

I’m writing this from Heathrow, having spent the first few weeks of January in the UK following my mum’s life-changing stroke. She had been recovering in hospital for six weeks, and it was a call from the hospital to discuss moving her into a nursing home that got me onto that long-haul flight in late December.

As with most families, we play different roles, and this was my time to step up. I had one goal: to get mum back into her own home, with sustainable support.

Anyone who has been in a similar situation with their parents will probably appreciate the unexpected shock, emotion and overwhelming sense of responsibility you carry when they lose their agency, even though we’ve known for years that these days will come.

So I blundered through the first week of daily hospital visits — teary, worried, getting used to a new version of my mum, and with no idea about how we were going to manage this as a family. Mum’s situation was a bit worse than my family had told me or had maybe realised.

Suddenly I found myself on the receiving end of service delivery, from a bureaucracy I knew nothing about, in a state of family stress, and with an urgent need to get things in place while I was in the country.

Once we had made it clear we did not want to follow the care home pathway and were quite clear on what we would like to achieve, we were introduced to a social worker, Audrey-the-Game-Changer. That was on the last Wednesday in December.

Understanding my sense of urgency, Audrey arranged a meeting for January 2 with mum, our family, the occupational therapists, the mental health team, and social workers. We were given professional opinions on mum’s status; then, with our goals front and user-centred, Audrey took detailed notes on what we thought a good day would look like for mum at home and the support we thought she would need to achieve that.

Audrey and her team developed a care plan within 24 hours and put it to a range of providers in the market. Within 48 hours of the meeting, she provided us with three offers and we happily accepted one that could best meet our preferred daily time slots, and level of service, and that could start providing these services four days later.

With a date set for ‘care at home’ to start, the hospital discharge team kicked into action, and somehow the pharmacist, occupational therapist and mental health nurse all found me during my visits to the hospital, to share the plans they had put in place for mum, and told me to expect calls from their community counterparts.

I received all those calls the following day. The local chemist explained the list of Mum’s medications, why she was taking them and how they would be prepared for her and delivered to the door each week.

The stroke support team called with a crisis number to call should we need advice or urgent support; a trades team arrived to install a key safe at the front door that all care and emergency services can access if they need to; and someone else arrived to install mobility aids throughout the house.

Not only that, but District Nursing called to say that given the situation, they would come to the house twice a week to dress my dad’s chronic wounds, rather than him continuing to visit the clinic.

Mum arrived home on January 8, six days after the meeting, with everything in place, and everything has run smoothly since.

My experience as a user of an unfamiliar service delivery system has left me astonished.

I asked for a user-centred solution on behalf of my Mum … and within a week we had one.

All I had to do was ask and then accept the support that found us.

Key features of this experience were that they provided us with:

one person to support us all the way through

seamless service delivery across all levels of government

user-centricity that made all the difference, even though the user at the centre was very vulnerable and could have been easily persuaded to accept anything

a sense from every person who helped us that they really wanted the best for my mum and the family — and had the power to help us get it.

We didn’t complete any forms, go to any further meetings, submit any applications, or need to understand which level of government or regional authority was providing the support. I signed one document confirming that the care plan proposed reflected the discussions we’d had and that if required, we’d contribute to costs.

Every step of the way, mum was heard and her contributions were included despite her brain injury. They spoke with mum first and us second, and the service providers did the same.

I can only give full marks, rate it as highly as possible, and be inspired by how they did it.

As someone who works with organisations often seeking to improve their service delivery, this experience has certainly lifted the bar for my expectations of what can be achieved when you put your mind — and your mindset — to it. I’ll be pushing my clients to go that little bit further, to develop a bit more empathy, to rethink some of the barriers in place, and to empower the frontline just a bit more

But wait, there’s more…

Audrey also told me about an allowance my parents should have already been claiming and sent me the links to the form. Yes, it was a long-form, 61 questions asking about capacity and capability. It was very specific and gave me a sense that the assessor would have a good understanding of where the challenges lay and where they didn’t. At the end of each section, they asked if there was anything else I’d like to tell them, allowing me to provide context and a more individual assessment, with a generous word allowance.

The downside of this form was that it had to be printed, signed and posted. So, my first stop was the local library, which sent me next door to the Working Well hub. This is a local government hub that is there to help. Full stop.

I walked in, explained my problem, and they solved it. Right there, I emailed the form to Lorna, we had a cup of tea while it printed and she certified some documents for me (as I was applying for someone else). There was no queue, no ‘take a number’, no ‘make an appointment’, no waiting, no ‘we only solve local government problems’, just friendly help, for anyone to use. Their main role is to connect people to services and support as they need it.

Despite all the tech-enablement that sits behind these experiences, it was the people-enablement that made it work, that’s what made the difference.

So, there’s a little insight into my UK public service user experience. Maybe I was just really lucky because it was pretty good. Good enough to write about.

The biggest impression? It felt personal, in the best possible way.