Ageism in the workplace — are we valuing or just ‘managing’ experience?

Originally published in The Mandarin

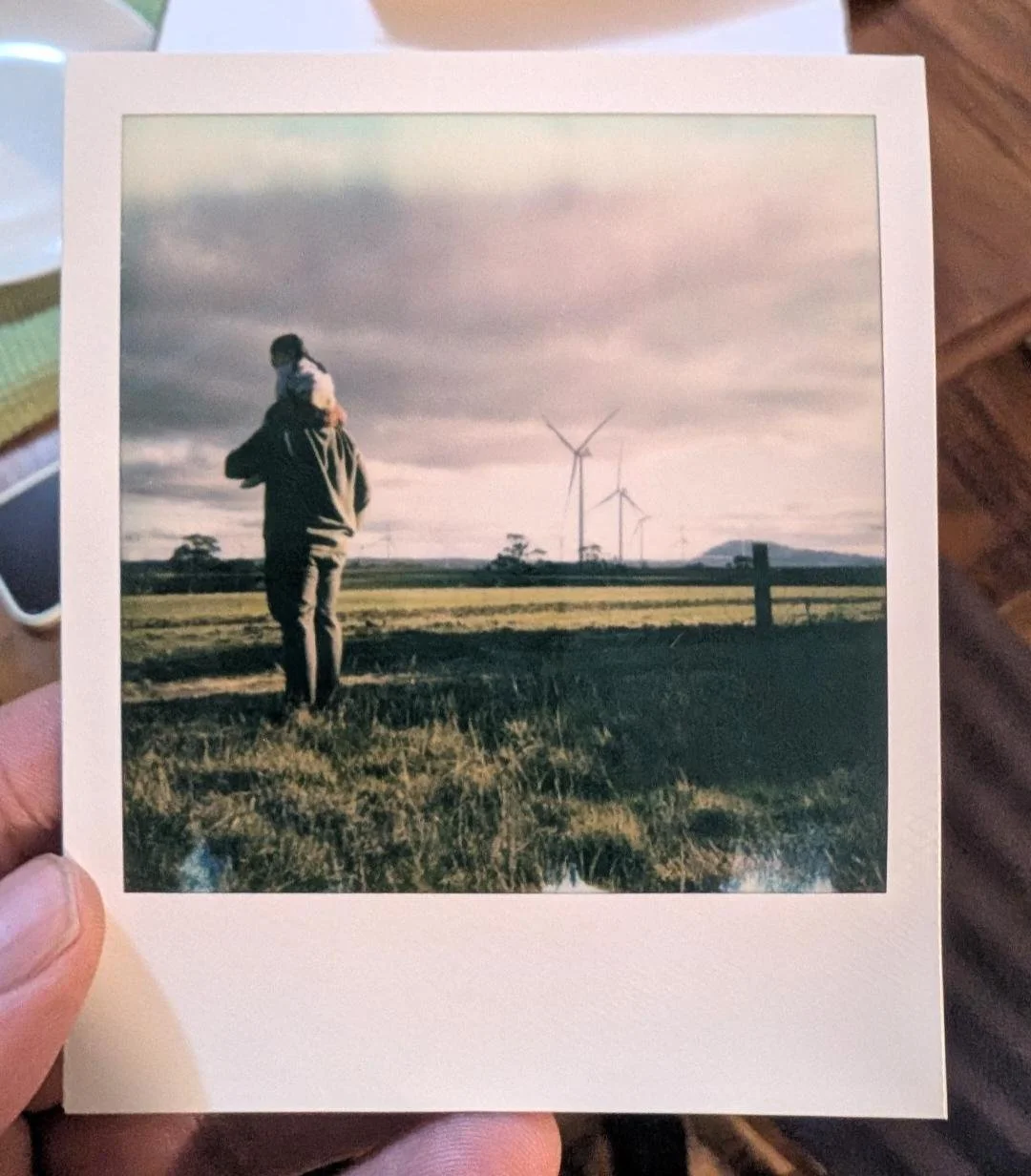

A one-size fits all approach to performance management may not accommodate the needs or value of many members of the 50+ workforce. (shurkin_son/Adobe)

Learn – Earn – Return.

It’s a familiar saying with the 50-somethings, reflecting stages we go through in our professional lives, with the third stage kicking in at different times, often depending on how well the second stage is going.

For the past few decades, it has been widely accepted that you’d spend your early career learning as much as you possibly could, doing some work ‘for the experience’ until you could launch into the serious earning stage of your life where you use that experience to build your wealth. Then once that need had been satisfied you’d be more inclined to ‘return’, or give back to society or the community.

For those of us not in the Buffet, Gates or Lowy bracket, where philanthropic donations service this ‘return’ need, we seek to leverage our experience in other ways to support or contribute to the wellbeing of others — while often still wanting or needing to earn.

This is the paradigm we 50-somethings have lived in for most of our lives, unlike the emerging leaders — we’re talking about millennials again — who stereotypically don’t want to wait until their lives are sorted out before they contribute more effectively to the greater good and are more likely to want to learn, earn and return throughout their lives, right from their teenage years.

So what does this mean for inter-generational diplomacy and management?

I’m asking this particular question because it seems to find tension in the context of performance management for the over-50s workforce. This has come to my attention because I’ve had two private sector and two public sector 50+ friends comment to me these past few weeks on the seemingly irrelevant or frustrating hoops they are being asked to jump through to satisfy ‘standard’ performance-management requirements.

When they’ve questioned the relevance of, or need for, the process, their powers-that-be reflect that it’s HR driving the process and that they too are cogs in the wheel — nothing personal. Hmm, not the response of a good manager.

It is worth noting that these are people who, over the past three decades, have advised ministers, led major programs and communication campaigns, been involved in historical international events, met and supported recognisable leaders, managed multiple teams and have been part of multiple transformations. They have learned a lot, earned enough and, with the right systems in place, would return even more.

The right systems often aren’t in place, though. From a 50s perspective, it seems the systems have been designed only for those in the earlier stages of their career, where learning is the key organisational priority, earning is an important motivational driver – and a good performance evaluation is tied to an increment or bonus.

Here’s the difficulty.

Situations, motivations and priorities usually change over time and a one-size fits all approach to performance management may not accommodate the needs or value of many members of the 50+ workforce. But as a manager, you can’t assume that.

So there is work to be done to understand if your more mature team members are in the learning and earning phase or if they’ve moved into the returning phase.

In the first two stages, one size likely fits them. If they are able and willing to move into the returning stage, they are likely to need different motivations and a role where their experience is leveraged, their value is better recognised, and they are treated respectfully. Don’t get me wrong, they still want to be paid appropriately.

The people I have spoken with largely fall into the returning group, and with their wealth of experience, they are being asked to prepare dossiers and explanations of the value they bring to the business, as part of the ‘standard’ performance management cycle.

From a 20-something perspective, that makes a lot of sense, it’s a great opportunity to share achievements, ambitions and growth trajectories as leverage for more learning opportunities and increment increases.

For someone who has a growing focus on ‘returning’, the performance evaluations that are intended to motivate and course correct can often demotivate, demoralise, erode confidence and devalue the person’s contribution – all unintentionally.

From a 50-something perspective, it’s a bit annoying, even insulting, noting that the person seeking this information is often the go-getting early-40-something.

Funnily enough we – in our mid-50s – remember being that person: quietly a bit ageist, a bit frustrated at the different approaches and ways of thinking, wondering why for some, career is one of several priorities rather than the key priority it often is during the 40s.

What we didn’t realise then, in our 40s, and I’m offering the hot tip now, is that the generational gap between 40 and 55 is the same as the gap between 25 and 40. With this in mind, I encourage every 40-year-old who is managing a team member in their 50s to reflect on just how much you can learn, witness, understand, experience, grow personally and develop professionally over a 15-year period.

So, managers of more mature team members: what can you do to make this better?

Harness that extra 15 years of exposure, experience, breadth and depth. Look at it as an opportunity rather than baggage.

Take a strengths-based approach: leave the script and understand what really motivates them, be open to goals that aren’t all about learning and earning, and be sensitive to how demoralising it can be to ask them to explain how their experience is relevant to the team (should have checked that when you employed them, BTW!). Instead, ask how they believe they can best contribute to the team and organisation given their broader and deeper experience of how much of the organisation works. Many are likely to suggest mentoring and coaching others to support their career development, over their own.

This needs to be balanced with an approach that recognises that life is long and not everyone plans to peak before their 90s, so share the opportunities for further growth fairly across the team — without making assumptions that some don’t want or need them.

When you’re facing a challenge, demands from above, transformation requirements or stakeholder conflicts, take your more experienced team members for a coffee and ask them if they’ve seen something like this before, how it played out, and if they have any advice for you.

Become more aware of what ageism looks like and step in if you see or hear it playing out in your team: it’s the comment that this is a nice job to wind down to retirement (just before she turned around a failed CabSub), or questions about retirement planning; it’s jokes about someone’s age, holding team activities that don’t cater for the diversity of the team, or dismissing lessons learned from ‘the last time this happened’. Subtle, but real.

My discussions with the more mature worker suggest that if you know how to harness it, you’ll get the benefits of experience, loyalty, networks, insights, support, coaching and mentoring, as well as the reliable technical expertise they have built up over decades.

Then, if decency, fairness and the law don’t motivate you to look more closely at any ageist practices in your team, you could spend a moment wondering how you would like to be treated in the not-too-distant future (it creeps up so quickly!) and note that those 20-somethings in the workforce will model how they include, respect and leverage your strengths in 15 years on how your treat those of your more mature team members now. Definitely worth thinking about!

I realise that I have presented half of the story in this column, and that a better understanding by the 50-something managers of the shift away from the ‘learn-earn-return’ paradigm would go a long way to leveraging the strengths of those following through. I’m opening the door here for someone to write the counterpoint!